Vaccine Misinformation Fuels Oregon’s Nursing Staffing Crisis

When Oregon’s largest hospital announced its staff members would be eligible to receive their first dose of the COVID-19 vaccine in the final weeks of 2020, a majority of its employees scrambled to receive their first dose.

"We had people in tears," said Dr. Marcel Curlin, an infectious disease expert at the Oregon Health and Science University hospital. "People were really anxious to get the vaccine."

Soon though, Marcel said the “party-like atmosphere” subsided once a bulk of the hospital staff received their shot, and afterward, vaccination rates stalled at 87%.

When Oregon Governor Kate Brown, a Democrat, issued a vaccine mandate to take effect in the state in mid-October, the decision not to get vaxxed left thousands of frontline workers vulnerable to more than just the virus.

The decision: receive the jab or walk out of their infirmaries doors for the last time.

The Gap

Experts say the mass exodus of healthcare workers across the state is partially fueled by the spread of debunked conspiracy theories about the shot online which targets dubious digital users.

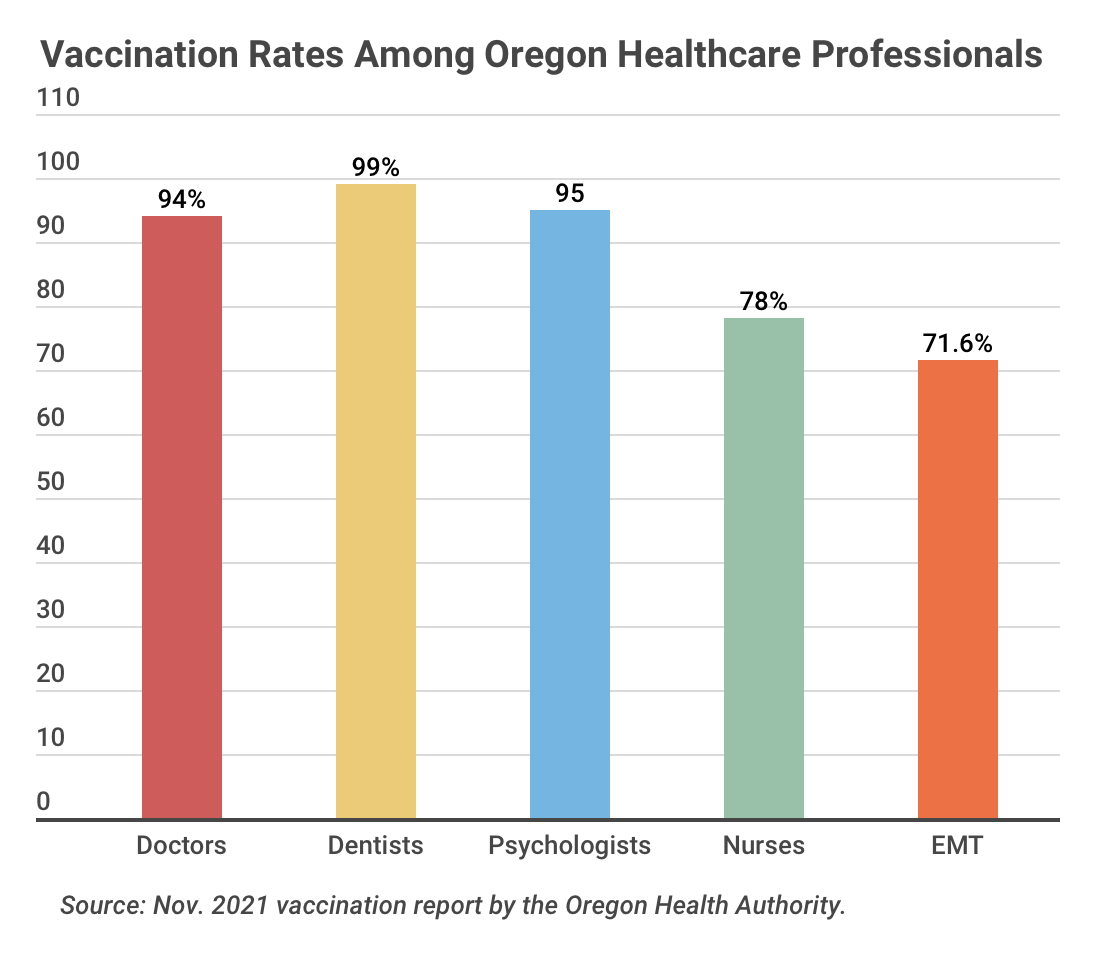

U.S. healthcare workers, by and large, have been vaccinated at higher rates than the general public, but data from the Oregon Health Authority found that education level within the medical industry affects employees' stance on the vaccine.

“There are people who are essential to the hospital, but they are not as informed about a lot of these health issues with the vaccine,” said Dr. Tara Kirk Sell, a senior scholar at the Center for Health Security at Johns Hopkins University. “So they may be more vulnerable to misinformation.”

As a result, Sell said that lower level hospital staff, such as nursing assistants and technicians, who have received less medical training are vaccinated at rates lower than healthcare workers like registered nurses and doctors.

The mandate and the resulting staff shortages come amid rising cases of COVID-19 in the state, where more than 700 people are hospitalized for the virus daily, according to the U.S. Department of Health.

The Oregon Health Authority reported that nurses have consistently ranked among the lowest sector of the healthcare industry for vaccination rates, with 78% of registered nurses having reported receiving both doses of the vaccine.

The Problem with Bad Information

In part, Sell said that this is because of the infodemic currently playing out on the country’s screens.

In America, more than eight-in-10 adults receive their news from a smartphone, according to a Pew Research study from January. Healthcare workers with ranging educational backgrounds are no exception.

Medical misinformation about COVID-19 has festered on social media since the onslaught of the pandemic, and researchers say it’s getting harder to differentiate between fact and fiction about the virus.

“From patients, I heard a lot of things that were way out there, like, 'I think the vaccine has [computer] chips in it,'” said Curlin. “In the medical community, I never heard anyone subscribing to these more far out conspiracy theories."

The reason for this, Sell said, is education.

“The more health literacy you have, the better defenses you have,” said Sell. “That way, you’ve already pre-debunked a lot of the crazy things you might hear online.”

Sell said that many of the rumors spread online about the dangers of the COVID-19 vaccine aren’t new, and are actually commonly recycled when health epidemics like the coronavirus arise. Similar fears circulated when vaccines were developed for diseases like the measles in the 1960s.

The most common concerns Oregonians cite for their vaccine hesitancy include fear that the shot was developed too quickly and doubts about its ability to ward off the virus, according to a study of more than 1000 residents across the state led by Dr. Benjamin Clark, co-executive director of the Institute for Police Research and Engagement at the University of Oregon.

But Clark said some conspiracy theories directly appeal to the emotions of those who are hesitant about the vaccine, and have been overwhelmingly successful in dissuading women in the healthcare industry from getting the shot.

“Most commonly, I hear about the vaccine’s threats to fertility for women,” said Clark. “These are fears that are not based on any scientific studies, but it creates an emotional response.”

In a state where just 12% of licensed nurses are men, debunked rumors such as these have the potential to impact areas within the healthcare system that are female-dominated. Often, nurses are not trained to recognize anti-vaccine propaganda and fake studies about the virus, said Clark, which leaves their health, and jobs, vulnerable

“Get the vaccine or find a different field”

Despite widespread anti-misinformation campaigns, a mounting number of healthcare professionals continue to hang up their stethoscopes in the face of mandates rather than be pricked by the needle.

“At the end of the day, no one can tell you the long term effects of this vaccine,” said Elizabeth Wright, a certified nursing assistant in Oregon who is not vaccinated. “Whether or not to get it should be a personal choice.”

Wright participated in a protest against the mandate in front of the Oregon State Nursing Board, and said that the vaccine was a good way of protecting oneself from the virus but that the governor's orders violate her medical freedom.

Since Brown introduced the COVID-19 vaccine mandate for state workers earlier this year, numerous lawsuits have been filed against her by Oregonians who say it violates their constitutional rights.

Early signs indicate that the mandate is boosting vaccination rates across the state, which has lagged in inoculating its residents— but not without a cost.

One Oregon hospital said that the percentage of its vaccinated staff jumped to 96% of all of its workers after the mandate was announced; nevertheless, for some, fear of the shot superseded looming threats of unemployment. Legacy Health lost over 800 workers when the mandate went into effect, forcing one of the state's largest healthcare providers to consolidate labs and temporarily close several of its urgent care facilities.

“I don’t think it’s fair that the frontline workers who were considered heroes last year without a vaccine, and with limited resources, are now being given the option to get the vaccine or find a different field of work,” said Wright.

In a state where there are just 11 nurses for each of its thousand residents, the nurse staffing crisis in Oregon didn’t originate with COVID-19 or its vaccine mandate. However, since the start of the pandemic, 86% of nurses at OHSU reported symptoms of fatigue, burnout and mental exhaustion, and 60% said they are considering leaving the profession, according to a recent survey by the Oregon Nurses Association.

Wright said if the mandate stands, she expects the staffing gap to widen.

Yet, experts say there’s hope for boosting vaccination rates among Oregon’s hospital support staff— which begins with having potentially uncomfortable conversations about our differences and arming nurses with the tools to recognize and fight COVID-19 misinformation online.

Because an overwhelming number of healthcare providers attribute their vaccine hesitancy to not having enough knowledge about the dose, the Center for Disease Control recommends hospitals host routine discussions wherein staff are able to provide input and express any doubts they may be having about the shot so that they can be addressed by informed personnel, rather than the internet.

“We’ve got to try to get as close as you can to their perspective and work from that point,” said Curlin, who has spoken to dozens of vaccine-hesitant OHSU employees. “Going forward, that has been hugely helpful in these conversations, but it's not a one size fits all approach.”

Post a comment